Oulu Museum and Science Centre produces, records and presents northern science, art and history. We promote cooperation around these themes in our region. With our work, we want to strengthen local identity by guiding and inspiring people in the present moment and nurturing what is important for future generations.

We handle official tasks and related expert services. Our main tasks are public work, creating collections and nurturing cultural heritage and scientific capital.

We are still building our English websites but you can visit our museums webpages. Our destinations opens doors to experiences that increase competence, understanding and pioneering.

Science Centre Tietomaa

Go on the website

Oulu Art Museum

Go on the website

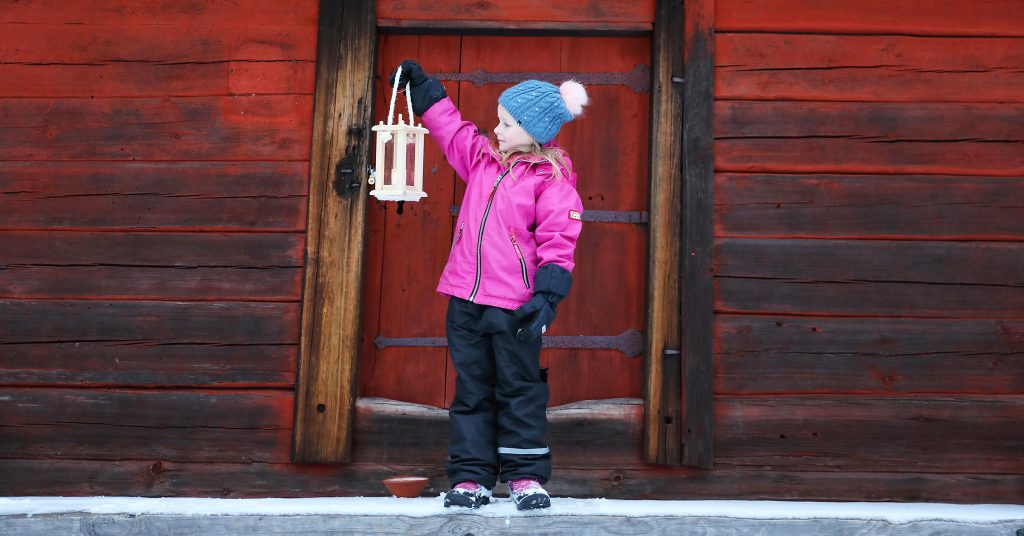

Turkansaari Open Air Museum

Go on the website

Kierikki Stone Age Center - pages will open soon

Northern Ostrobothnia Museum - pages will open soon

Sailor’s Home Museum - pages will open soon

Oulunsalo Traditional Village Museum - pages will open soon

Pateniemi Sawmill Museum - pages will open soon